Day 9: Moloka’i

In the morning I called Auntie Opu’ulani. If you recall, this is one of the people Janine, the helpful lady at the airport, had recommended I talk to. I got through to Auntie and we made arrangements to meet on Wednesday.

Then I called a boat tour place and made reservations to snorkel on Thursday. I cannot be on a tropical island and not snorkel; it would be unnatural. Molokai has a long, shallow reef surrounding it. You can get to the reef from the shore, but the snorkeling is better further out. So they say, anyway. I’ll let you know.

I had decided not to look up some of the other people Janine recommended, including Uncle Pilipo, who is a kupuna (elder) who knew a great deal about mo’olelo Moloka’i old tales of Moloka’i). This was mainly because I didn’t have Uncle Pilipo’s contact info, but also because I felt I was making good progress and didn’t want to get greedy.

Feeling pleased with these arrangements, we started up the road, heading for Halawa (hah-lava) Valley, looking for the ancient fishpond along the way. We saw a fishpond, but no sign that anyone lived nearby, so kept on going.

It became more lush as we went along, the dry, red-earth grassy areas giving way to thick stands of trees and broad-leaved tropical undergrowth. The road hugged the coast, and in places, there was little between us and the water except for rocks. Not long after the fishpond, the road became one lane, sometimes with room for another car to squeak by–and sometimes not. The road started to climb, and we began to see vistas of the ocean far beneath. We could clearly see the island of Maui across the channel.

I mentioned that Tom and I are acrophobic. But we differ in our reactions. I don’t mind hiking trails with steep drop-offs or driving roads with same. I don’t like climbing ladders, being on roofs, walking over transparent supports (you’ll never get me out on those glass platforms over the Grand Canyon), or actually being on the edge of a high cliff with no barrier between me and a five-second drop to eternity. Tom doesn’t like any of that, but he would rather drive if he is on a cliff road. He drives white-knuckled and sweating bullets, though.

So I enjoyed the drive, and Tom didn’t. He really is a hero sometimes.

There are people living out here, and even farms. The residences were scattered, but there was this tiny church along the way:

We passed this beautiful zigzag pole fence:

As we approached the descent into Halawa Valley, we could see two waterfalls pouring hundreds of feet down into the valley. I tried to take photos, but they were too far away. Finally, we got to to the valley floor, a rainforest jungle. There was a sort of public park building there, and then there was a dirt road to the beach.

Tom by now was quite ready to turn around and depart as fast as possible. There were three Hawai’ans sitting to one side of the road on a low rock wall. The one on the left was a heavyset fellow of middle age. The young man on the right was dressed in a short lava-lava (I don’t know what the Hawaiian word is; it’s a sort of kilt arrangement made of patterned cotton cloth), a shell necklace on a braided cord, and nothing else. The gentleman in the middle was elderly. (That means older than me. I figure he is about 76.) He wore unremarkable clothes and a faded baseball cap. He was very thin and his face under the brim of his cap was weathered. Neither Tom nor I can remember exactly what was said. I know we exchanged aloha, and I think they asked us why we were there. I responded that I was looking for mo’olelo Moloka’i.

The men to left and right looked at the man in the middle, and simultaneously said, “This is the guy you want to talk to.”

I leapt out of the car and walked up to the older man. He was shaking his head, so I said, “Come on, Uncle, please tell me some stories.” (Remember, “uncle” is respectful when speaking to someone older or wiser than oneself. The Hawaiians have great respect for their kupunas, unlike the typical American, who sees them as old and in the way. I’m liking Hawaii better every year.) The gentleman replied that he didn’t just tell stories, I needed to make an appointment. He insisted on this several times. I took this as a message that he took what he did extremely seriously, and he wasn’t sure that I did.

I didn’t press him, but told him I was meeting with Auntie Opu’ulani on Wednesday and snorkeling on Thursday, and leaving on Saturday, and in any case, my husband would not drive back down that road. At this point, the heavyset guy offered to drive me, which I thought was incredibly kind.

The kupuna finally asked why I wanted to know these stories. I told him I was a writer, and wanted to set my next novel in Hawaii. He asked what my last novel was about, and I tried to tell him. I found it amazingly difficult to summarize a 350-page novel, especially as I had no idea what his background was. He had as much trouble pronouncing Quetzalcoatl and Necocyaotl as I do with many Hawaiian words.

I have found that when I tell people I want to hear their stories, they are cautious. Once I say I am a writer, they open up. I am not sure why this is so.

He talked to me for quite a while about good and evil. He said everyone has capacity for both, and we each must choose which way to go. He also talked about not giving over your power to another person. He waxed so philosophical that after a while, I asked him if he was a kahuna.

“People don’t understand what kahuna means,” he told me severely. “Kahuna is an educated person. My grandfather told me we are all kahuna, just not everybody knows it. There are good kahuna and bad kahuna. You understand?”

I said I did. I hope I did. Mostly, I kept my mouth shut, and he kept talking. He often spoke in Hawaiian, which sounded to me like water running over smooth stones. Beautiful. He eventually stopped talking in abstract terms and began to tell me a story. He told it in the first person, as though he were the young boy in the tale. Seeing my puzzled expression, he said, “Now I am telling mo’olelo, you understand.” Here is the story, as much as I can recall, because I was listening, not taking notes. I have retold it, so it is in the third person:

A young boy was born in Halawa Valley, the youngest of seven siblings. He was chosen to be the cultural teacher (teacher is not the word he used, but it is close) in his family, the one who would preserve the ‘ohana’s cultural wisdom (‘ohana means family). He was not allowed to swim in the sea or go to the waterfall like his brothers and sisters and he was unhappy and thought this was unfair. One day his grandfather told him they were going to the waterfall, which is called mo’o-ula (red lizard) because a mo’o lives there. (Mo’o are mythical lizards. They were huge, and no actual beast of this sort has ever lived in the Hawaiian Islands. Some mo’o were kindly toward people–some not.) If you threw in a ti (pronounced tee) leaf in the pool beneath the fall and it sank, you were not allowed to swim in the pool because that meant the mo’o was in the pool. The boy wanted to know why they were visiting the pool, but his grandfather told him not to ask questions.

There were ti bushes that had been planted by the people all along the path, so the boy broke a leaf off as they walked. When they got to the pool under the falls, the grandfather broke off a big clump of ti leaves, fastened it to a stone, and tossed it in. “One ti leaf is not enough,” he told his grandson. The ti leaves floated around this way and that, then sank. This meant the boy could not swim because the mo’o was using the pool and anything could happen to him.

Then the kupuna began to relate things from his own life. He told me that when he was a boy, his grandfather told him that the beach at Halawa Bay was the burial ground of his ancestors. He asked a lot of questions, but his grandfather told him not to ask questions and took him to the beach (sound familiar?). The boy said he could see no graves. When the tsunami of 1946 washed out the beach, he saw the bones scattered all over the beach, uncovered by the ocean, and knew his grandfather was right.

His grandfather also took him to the falls and told him the mapmakers had made a mistake (again, no questions allowed). They called the falls red chicken falls (moa-ula) instead of mo’o-ula (red lizard). The grandfather pointed up to the falls and said, “Do you see a red chicken?” The boy did not. Then a mist came in, and his grandfather told him it was the spirits of his ancestors. When the mist cleared, the grandfather pointed again to the top of the falls. “Look again, what do you see?” He looked again, and saw the head of a huge lizard peering over the edge.

He then told me that he had told archeologists where to find ancient remains of firepits and fishponds. The scientists dated the fishpond at 650 AD, the oldest yet found in Hawaii. It is believed that Halawa Valley is the oldest continually occupied site in the islands. I haven’t checked this, but it seems probable, if what he told me is true–and why not?

The kupuna had told us that he would need to leave soon, as he was taking his haole (pronounced how-lee, means Caucasian) son to the airport. After some time, a young, blond man came walking down the road and my kupuna told me he had to go.

I asked him what his name was.

“Uncle Pilipo,” he replied.

I stared at him. “You’re Pilipo?” I stammered. “Janine Rossa told me to find you.”

“Well, you found me!” he replied, climbed into a truck, said “Aloha,” and drove away.

OK, there’s only 8,000 people on this island. But I was completely gob-stopped. Of all the people who might have been waiting by the roadside at a place we arbitrarily decided to visit, how likely is it that it was one of the three people I had been told to see?

While I am being woo-woo, I noticed that on the Big Island, when I told people about my experience in Kilauwea, they were quietly accepting. Here, they are skeptical, which is interesting, because Moloka’i is supposed to be the island where the magic still exists. Perhaps Pele has been gone too long from Moloka’i for people to pay much heed to her. I think most Hawaiians here are Catholic, judging by the number of Catholic churches, which, given Father Damien’s popularity, is not surprising. I don’t think they want to talk about the old gods much.

So Tom and I started back up the narrow, winding road, Tom not being interested in going to the beach or to the falls. (I was, but I understood his need to get back to nice, flat land as quickly as possible. He had sacrificed enough already.) I missed a lot of fine scenery on the way back because I was frantically typing Pilipo’s stories into my iPad. I had taken no notes at the time because I was trying to concentrate 100% on what he was saying. (It also seemed like a bad idea to ask questions given his stories.)

As we passed the ancient fishpond, I spied something that looked like an old Hawaiian hale, or house, near the pond, and some sort of palm-thatched structures tucked under the trees. There was a young woman talking to the passenger of a car that had pulled off the road. I got Tom to stop (we were at sea-level again, so no problem), and told the woman I was looking for Ray Naki.

“You found him,” she said. She pointed at a thatched structure under the trees. “He’s over there.”

I walked in as though I knew what I was doing (Tom was parking). There was a Hawaiian about my age with shoulder-length gray, curly hair, wearing a traditional loincloth (malo), a large bone fishhook like the New Zealanders make, hanging from a thick, braided cord, a bemused expression, and nothing else.

I said, “Your niece April in Captain Cook said I should look you up.”

He looked at me blankly. “Who?”

Ulp. “Are you Ray Naki?”

“Yes, that’s me. Who did you say?”

“April, April Qina. That’s her married name.”

He pondered that for a minute, then his face cleared. “Ah, ‘Apilela. That’s her name!” (‘Apelela is April in Hawaiian.)

He wanted to know why Apelela said I should see him, but I couldn’t tell him because April never told me. I just blindly did as she had suggested. I honestly never questioned why, to tell the truth, and had no particular expectations, which has been my modus operandi on this trip. I certainly was not expecting a loincloth-clad man living in a thatched hut.

Tom came in from the road, and Ray pulled three eyeshades hand-woven of palm fronds from a supporting branch of the lanai, donning one himself and offering the others to us. We put them on as directed and he invited us to sit at the picnic table.

I should describe the place before going further. The fishpond is enormous, maybe two or three hundred yards across, constructed of low lava rock walls that begin high up the beach and extend into the calm waters quite a way, making the pond more or less circular. The walls are frosted with pieces of white coral. There is a “gate” where fish can swim in or out. On either side of this gap, there are bamboo poles with clusters of coconuts. There is a similar structure on the inland side of the pond, standing in the sand. A small, white power boat floating on the waters of the pond was anchored to the shore by three rocks.

When I walked into this establishment, I was greeted by a pack of medium-sized, short-haired, golden-brown dogs, many with ridged fur down their spines. There were also a couple of vaguely chihuahua-looking dogs, though they were the same color as the others.

They greeted me by licking my hands and crowding around my knees. I wondered if they were related to the “poi dogs” the ancient Hawaiians used for food. I looked this up and found that the poi dog is extinct. The Hawaiians fed them on poi, the mashed and cooked root of the taro plant, which is used as a condiment here and is pretty much pure starch. So the poi dogs didn’t chew tough food and their skulls became deformed through muscle disuse, becoming flattened. They were described as fat, stupid and slow. Often when a child was born, he was given a poi dog. If the child died in infancy, the dog was killed and buried with it. If the child survived infancy, the dog’s teeth were pulled and fashioned into a protective necklace for the child. So the poi dogs are probably better off extinct, poor things.

There was a frame for a traditional hale, but it was unthatched at present. The kitchen–a camp stove and picnic table–was set up under a thatched lanai (and by “lanai,” I mean nothing fancier than a shelter). There was an old international cargo container with doors cut into it next to the lanai, apparently to provide protection from rain and wind. The lanai was hung with fishing nets and other paraphernalia. (But Ray has a cell phone. He likes to play the unsophisticated “native,” I think, but he is a sharp old fox.)

A couple of small children, including a fat baby in diapers, were wandering around. They were some of Ray’s five grandchildren. He lives with his wife, daughter and son, grandchildren, and I don’t know who else. The two-year-old went down to the fishpond with me and dragged away the stones that secured the boat anchor. I think he wanted to show off the anchor to me. His grandfather roared at him in Hawaiian, and I didn’t need a translation.

Ray’s Hawaiian name is Lei-mana, the powerful lei, so I will call him that. He is the brown of medium-roast coffee beans, big-bellied, but firm. Because of his attire, I was also able to observe that he has firm, smooth buttocks.

Lei-mana used to be a construction worker, but gave it up to pursue a more or less traditional lifestyle at the fishpond. He fishes the pond and his ‘ohana has a taro patch at Halawa Valley. He teaches school children about how their ancestors lived–also hula and the Hawaiian language. I gathered that in addition to school field trips, he has visitors from other areas of Polynesia, like New Zealand. A Maori from New Zealand gave him the fishhook necklace he was wearing.

Conversation with Lei-mana was somewhat awkward. He has a way of falling into silence for a while, then coming at you with questions. Yet he frequently did not answer my questions, greeting them with thoughtful silence. Then he would start talking about something unrelated. As it was a disjointed method of talking and I wasn’t taking notes, I have noted most of what I remember already.

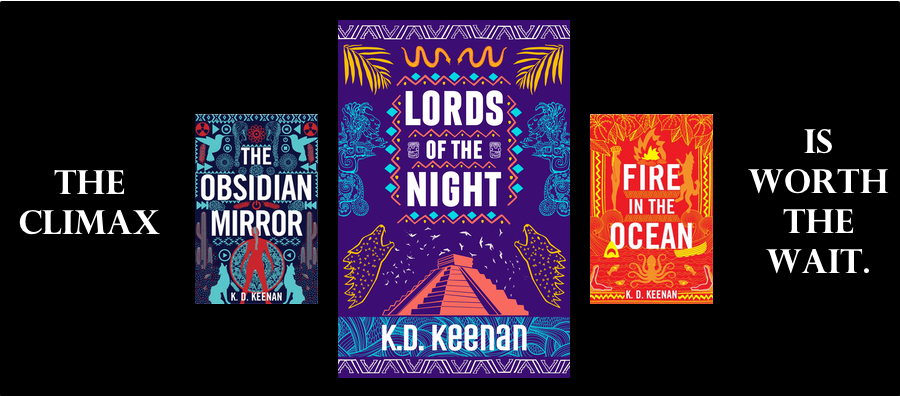

I gave Lei-mana April’s phone number and took his address so that I could send him a copy of “The Obsidian Mirror” (I have made this offer to anyone who has helped me on this trip). I also offered him some money (as I did Uncle Pilipo), because Janine advised me to do so.

“Don’t think they will be offended,” she told me. “They won’t be.” So far, utterly true.

Lei-mana asked if we wanted to return the next day and learn what he teaches. We agreed to come back at noon the following day. I leaned forward to kiss his cheek as Janine had instructed me, and then Lei-mana said, “Here is the old Hawaiian way to kiss, nose to nose and forehead to forehead,” and proceeded to do just that. We removed our palm shades, but Lei-mana insisted they were gifts, so we took them.

I was a bit overwhelmed at this point. We stopped for a very late lunch at Paddler’s Inn. We ordered the day’s special, Chinese chicken salad, which bore no resemblance to any dish by that name we had ever eaten previously, and I had another excellent daiquiri. Then we stopped in town for dinner makings and went home. I wrote furiously all through lunch, then started writing again when we got back to Paniolo Hale. We ate leftovers for dinner because we were tired, and then I wrote some more until about 10:30 pm. I was making lots of mistakes by that time, though I had only journaled through Uncle Pilipo, so I joined Tom in the enormous humid marshmallow of a bed and dropped into a sound sleep.

What an adventure! Someday ask me about the Hawaiian teachers that Jonathan had in the 5th grade in Palo Alto and the trip to Hawaii we made with them, and the class, as teacher’s aides. We met some real old timers and stayed the day with their relatives. A simple, but deep experience of Hawaii like never before.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would LOVE to hear of your Hawaiian experiences, Dina! We should make plans to get together soon.

LikeLike

Thanks to your descriptiveness I was cowering in the back seat on the drive up the mountain. I do wish you’d adopt veni, vidi, vici style of writing for that. The people you meet are fascinating. and there’s obviously so much from their tales you can weave into your own book. Carrying a history forward and sharing it with those who would otherwise not hear it is tremendous.

I hope you carry on enjoying the trip but try to stick to flat ground please from now on.

xxx Humongous Hugs xxx

LikeLike

I didn’t see you back there, or I would’ve told Tom to slow down! (Actually, if he had gone much slower, we’d still be on that road.) Thanks as always!

LikeLike