Day 10: Moloka’i

I awoke about 6:00 am, as I have been doing for a while. It was still dark. I went downstairs to make some excellent Moloka’i-grown coffee, then began writing, trying to catch up on our adventures with Leimana. We didn’t have to be at the fishpond until noon, so there was plenty of time to write, for once.

The drive to the fishpond is about an hour. There aren’t a lot of roads on Moloka’i, and no stop lights at all. The pace of life here is relaxed, and people are patient. Vehicles always stop if you are trying to cross the road. When you pass someone on the road, you wave whether you know them or not. People always say hi when they encounter you (or aloha). When you ask for directions or information, they drop everything to attend to you. It’s very like New Zealand in that respect. Not that the people of the other Hawaiian Islands are unfriendly or rude; there’s just a lot more “aloha” on Moloka’i. (Aloha means hello and goodbye, but it also means “love.”)

We arrived a little after noon. Leimana, in malo and fishhook necklace, was at the pond waiting for us. His first lesson was a lot of Hawaiian words. I did not retain all of them, but I did get a few questions answered.

I didn’t ask these questions; Leimana never answered a direct question with a direct answer. But he inadvertently defined the difference between “mauka” and “mauna,” both of which I understood to mean mountain. As it turns out, mauna, as in Mauna Loa, the volcano, means big mountain. Mauka (as in the common usage “mauka-side,” or toward the mountains), means smaller mountain. Then there were words for successively smaller hills and mounds, which I don’t remember. Except for pu’u, meaning a small hill, but this is used for other things, as we shall see.

Leimana was writing these words in the sand with a stick. He has lovely, clear sandwriting, like a schoolteacher.

I also had been wondering what a pi-pi-pi looked like. Pi-pi-pi means “small-small-small.” In Hawaiian, when a word is repeated, it creates an emphasis. So pi-pi-pi means extremely small. I knew they were a small mollusk that people ate. Leimana had a number of of these clinging to the walls of the fishpond. They are small black sea snails. (I told you I was nuts about shells.)

I asked about the clusters of coconuts at the fish gate. He gave me a rambling answer about coconuts symbolizing food, therefore home, therefore hospitality. I am beginning to understand that Hawaiian is a highly metaphorical language. All languages have metaphors (I think), but in Hawaiian, you might talk about the fishpond as a pu’u, small hill, because it is rounded, and because you might also call someone’s prominent belly pu’u, and the fishpond also fills the belly. Someone like me might easily misunderstand, but to a Hawaiian, it would be obvious.

Leimana demonstrates the way to place rocks for a fishpond. He says hula builds up the right muscles for this.

Which means I have no hope of actually learning Hawaiian. Which is probably OK. I have promised myself for years now that the next language I learn will be Spanish, which is a much better choice in California.

Leimana also showed us some hula moves and explained what they mean. Hula that men perform is quite different from the gentle swaying of women’s hula. His movements were decisive, abrupt, masculine, conveying the blowing of wind, rough water, paddling a canoe, fighting–but nonetheless graceful. He said hula made him strong, so he could lift the rocks when repairing the fishpond. He also said hula was originally performed only by men. I asked when women started hula, but he told me to ask Auntie Opu’ulani. Another direct question successfully deflected.

Somehow, we got on the subject of the Pacific gyre, which is actually one of the reasons I’m in Hawaii. Leimana didn’t seem to know what that was, so I took his stick and illustrated how the currents in the Pacific form a gyre, an immense circular river in the sea. In this gyre, plastic has accumulated over the years from dumping, people leaving junk on beaches all over the Pacific, maritime accidents, carelessness, etc. This is all swirling around in the gyre, which is often referred to as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Wikipedia says of its size, “Estimates of size range from 700,000 square kilometres (270,000 sq mi) (about the size of Texas) to more than 15,000,000 square kilometres (5,800,000 sq mi) (0.41% to 8.1% of the size of the Pacific Ocean), or in some media reports, up to ‘twice the size of the continental United States'”.[20]

When I first heard about this, I thought, “Someone could probably make money by scooping up the plastic and recycling it, and that would help clean it up.”

But there’s a catch. The plastic in the gyre has been broken up into tiny particles, some microscopic. It’s not as if someone can just scoop up the water bottles and sand buckets. And there are tons and tons of this stuff out there.

This enormous pile of particularized plastics is leaching chemicals into the water that are ingested or absorbed by sea life of all sorts, which means that it is coming back to us in the form of sea food. Fish and birds ingest particles, thinking they are food, which kills them.

And Hawaii is smack dab in the middle of this. There’s so much plastic out there that accretions of plastic, coral and rocks have started washing up on the once-pristine shores of the Hawaiian Islands. These have their own name, “plastiglomerates.” Kamilo Beach on the Big Island is littered with tons of garbage from the gyre because of the currents there.

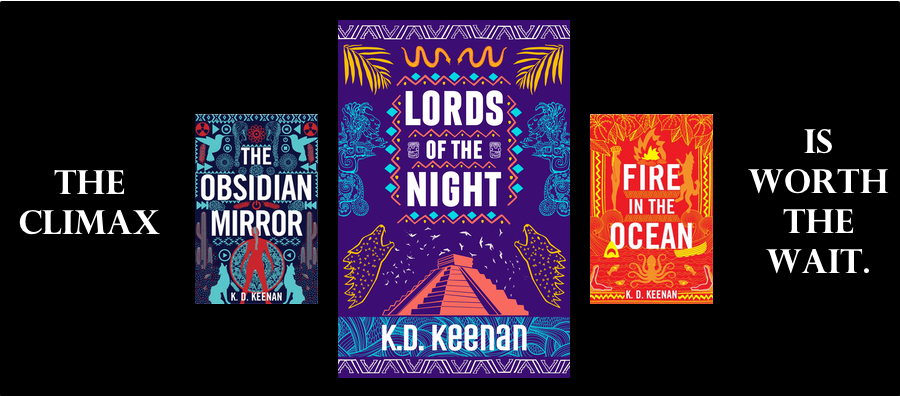

I told Leimana that I wanted to use my next book to help educate people about the gyre and the tons of plastic in the ocean.

Leimana was horrified. “What can I do?” he asked.

“Don’t use plastic,” I replied, but there’s really nothing he can do. It will take an enormous effort and a lot of ingenuity to solve this problem. People are working on it–that’s the good news. The bad news is that we use plastic in increasing amounts all the time. It’s handy, cheap, and incredibly useful, and many people can’t afford alternatives. Check out the price of a nice wooden table and chairs for your toddler and then compare that to the price of a L’il Tykes set made of plastic. Price-wise, plastic wins every time.

Leimana pointed out a large rock, standing by itself in the ocean. He called it a honu (turtle). I figured there must be a mo’olelo there, and asked about it. Leimana told me about the tragic love between a woman from Kaulapapa (the peninsula where the leper colony was and is, but this was long before), and a man from the other side of Moloka’i. They each got in a canoe and tried to meet in the middle, but the sea was too rough and they wound up drowning. He never mentioned the role that the turtle rock played in this. (I found out later from someone else, but I can’t tell you. More on that in another post.)

During the course of the conversation, we discovered that the fishpond belongs to a “rich lady.” Apparently she is fine with Leimana living there–indeed, there are other ancient fishponds quite nearby, and it is clear that he has restored, maintained and improved the pond he uses, so why would she not? He doesn’t get paid to teach the children or the groups that come through to learn from him (although donations are cheerfully accepted). He gets a bit of money from the government, and otherwise lives on fishing, taro farming, eggs from a relative that keeps chickens, and so forth. It seems to me that he is more than repaying whatever he is given by preserving his culture and teaching it to others.

We finally parted. He offered to treat us to lunch, but I was afraid he meant to spend money on us, so declined. It was long past lunchtime, so we drove to a little grocery along the highway that had a food counter. It’s definitely a local hangout, called Goods ‘n Grinds. They offered deer burgers, the first I’ve seen so far, and we have tried pretty much every restaurant on the island by now. Though half the menu on offer was burgers, they were out of burgers that day. The special of the day was beef tostadas, and we each got one. We sat at a picnic table in the shade and ate our tostadas. The young lava-lava wearer of Halawa Valley drove up in a truck and we exchanged aloha. We also saw these gorgeous birds:

They look like cardinals wearing woodpecker costumes. They are, in fact, crested cardinals. I tempted them closer by throwing some tostada shell crumbs on the ground, which were also appreciated by the ubiquitous blue doves.

I wanted to see the forest park where the trail to Kalaupapa begins. We had no intention of hiking the trail, for reasons already stated, but I knew it was a forested upland area, and very different from the scrubby grasslands of the area where most of the island’s population lives. The road seems to climb gradually, but goes to about 2,000 feet above sea level, where it ends in Palau State Park. It ends for a good reason–the next step is 2,000 feet straight down.

There is an overlook at the top of the pala from which you can see Kalaupapa. It’s like being in an airplane, and you must be able to see a 100 miles or more out to sea.

This is one of those things Tom doesn’t like (though that may be an understatement). I was fine with it because there was a nice, substantial rock wall separating me from the drop. Tom sat with his back against a large tree, across the path that skirted the wall and declined to come any closer. I admired the view and took pictures.

We walked back to the parking lot through the pines. The pines are unusual, with soft needles fully a foot long, giving them a “Cousin It” appearance for those who remember “The Addams Family.” I had earlier seen some coil baskets made of these needles in a gift store. I have seen pine needle baskets before and admired them, but these needles must have been particularly well-suited to basketry. The two baskets in the otherwise junky gift store were very well made and decorated with small shells. The one about the size of a hummingbird’s nest was priced at $100, so it was safe from me.

It was also cool in the forest–so cool it made me wish I had worn warmer clothes (not that I have warm clothes with me.) As a matter of fact, it has never been uncomfortably warm and is often downright cool, especially at night.

Then we went to look at the other attraction up here. It was indicated by a sign that read, “Phallic Rock.” This trail, unlike the concrete path to the edge of the pali, was unimproved and rather rough. I regretted not having changed from flip-flops into walking shoes, but managed OK. Tom, believing we were getting near the pali again, decided to wait for me on the trail, but I went to the end.

Yup, it was kind of phallic all right:

Someone had left an offering in a bowl in the rock, carved either by man or nature. The rock is sacred to the Hawaiian people, who viewed sexual mana as powerful and beautiful. Ku, the chief god, also means “erect,” in every sense of the word, including standing tall agains aggression or oppression. I often see offerings left at heiau or other sacred places.

However, some asshole named Jesse carved his name into this rock. I can only imagine what his punishment will be. Probably he’ll be doomed to live his entire life as a stupid person, with all rights and privileges thereto. If I had my way, the centipede I mashed the other night was named Jesse.

The rock was nowhere near the edge of the pali. I picked my way carefully down the rough trail, but Tom wasn’t interested. Tom was interested in descending to lower, flatter ground.

Then we drove back into the metropolis of Kaunakakai to get some groceries, then back to the condo. We were actually too tired to cook again and made do with cheese and crackers. I was even too tired to write!

I have really been enjoying these posts. I spent one week in Hawaii in 1987. I don’t expect to get back. But I am very interested in the islands and the people.

LikeLike

Tank you, Caroline. I have one more to go to wrap up the trip–but we’ve been back for a few days, and I just haven’t had the time. Maybe today.

LikeLike

Marvelous to read. I had a good laugh at the difference in long-range photo positions…Tom’s then yours. I know you both!! You both are so gentle with each other. That’s a trait that comes from being together for a long while, I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dina, I’m glad you enjoyed it. How nice to know you are following our adventure!

LikeLike

Sounds like an intensely busy time again but full of knowledge gleaned by you and from you. You’re having an amazing time there and I’m sure the information you’re gathering will make you book a best seller.

xxx Huge Hugs xxx

LikeLike

I just hope it’s a good book, worth reading. If it was a best seller, I wouldn’t object much, though!

LikeLike